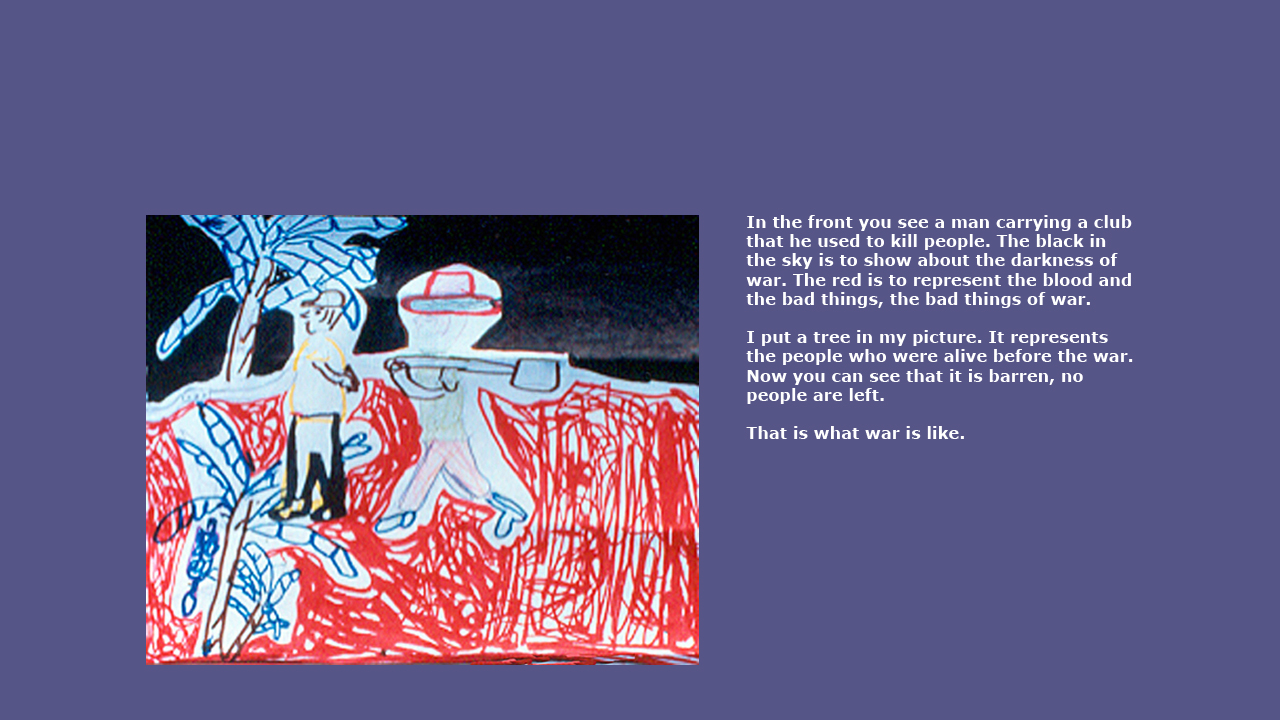

Unit 4 - What War Is Like

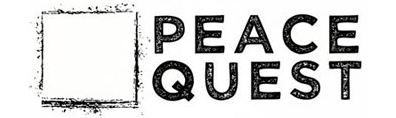

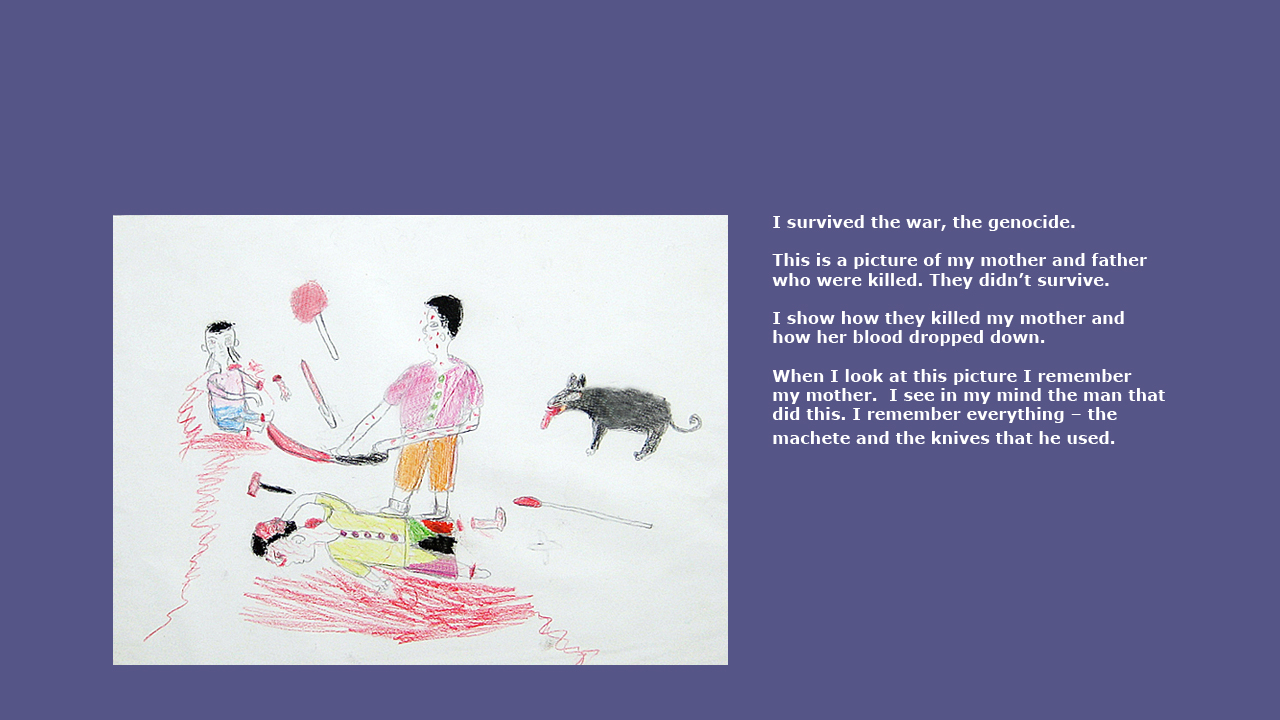

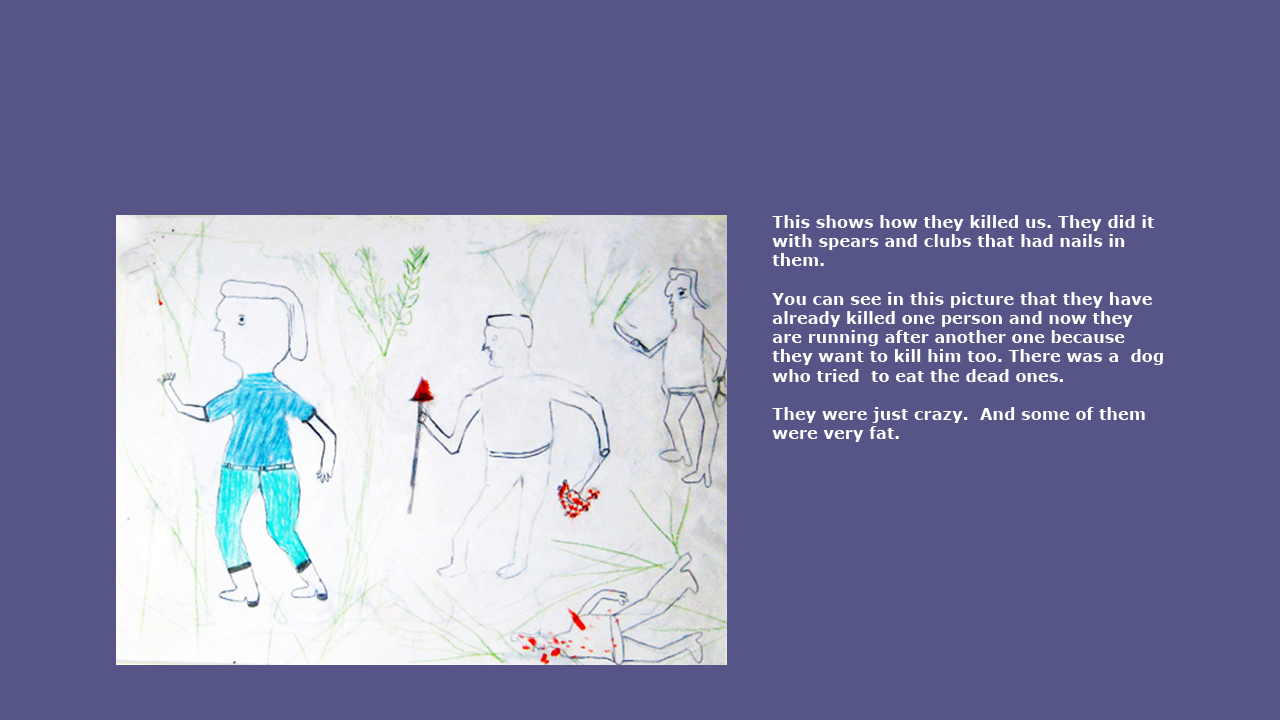

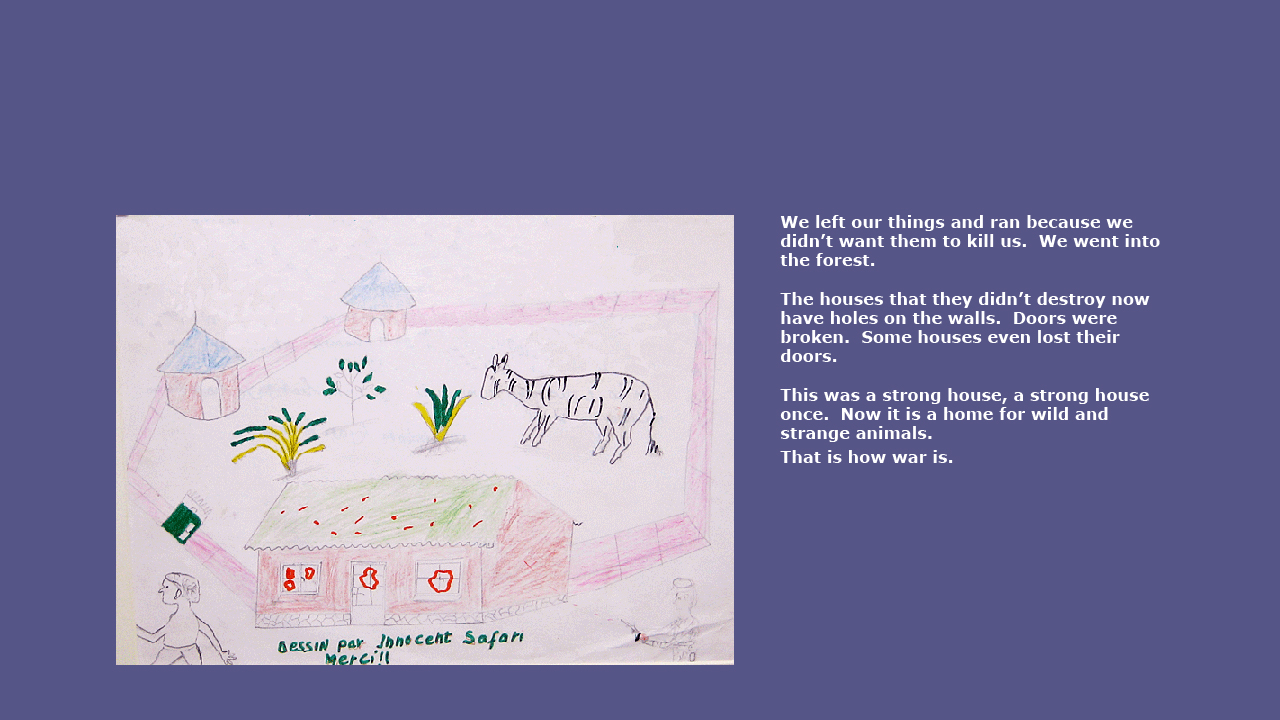

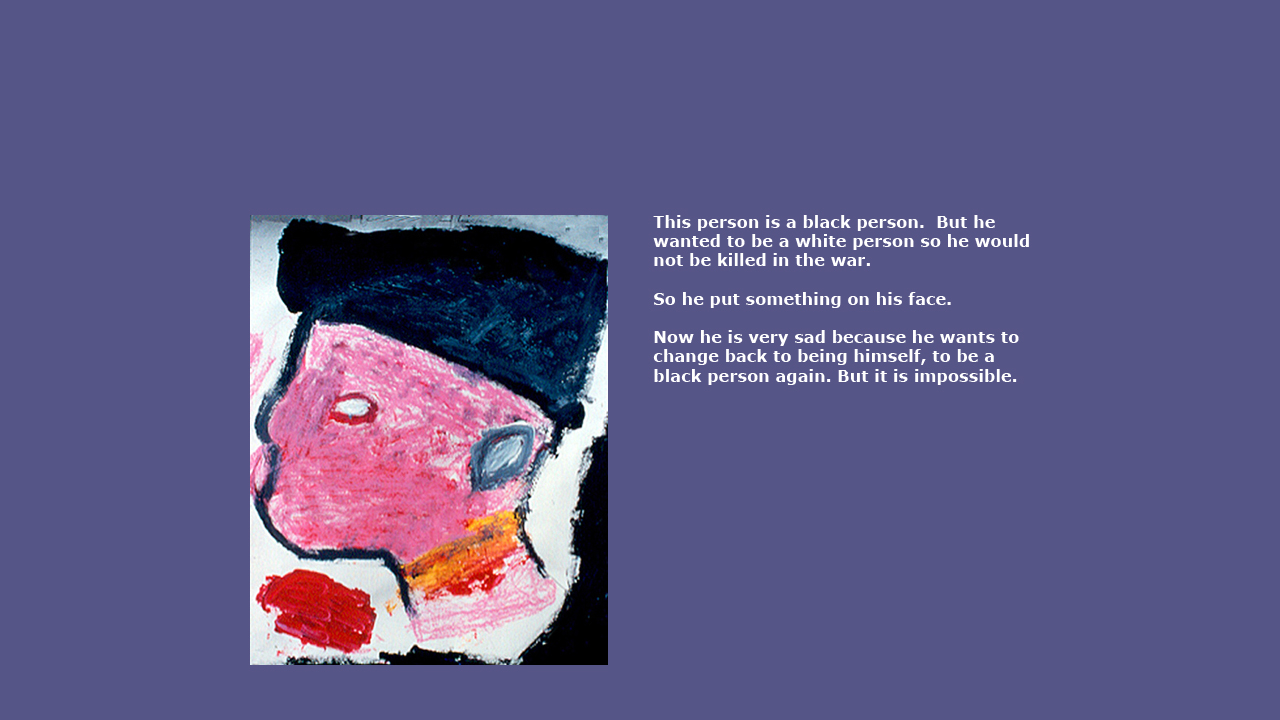

Artwork and writing by youth survivors of the Rwandan Genocide.

The materials in this gallery were produced in art workshops conducted in Nyamata, Rwanda, in 1997 and 1999. Across the courtyard from the workshop was a former Roman Catholic Church which was the site of one of the genocide’s worse massacres. The church was deconsecrated in acknowledgement of the massacre and also because the local priests had helped the killers rather than providing protection for the Tutsi victims. This church later became a place of memory with over 25,000 skeletons being placed in a crypt that was constructed under the building.

All the participants in this workshop had lost their parents in the genocide. They were struggling to cope with this loss while also providing support for their younger siblings.

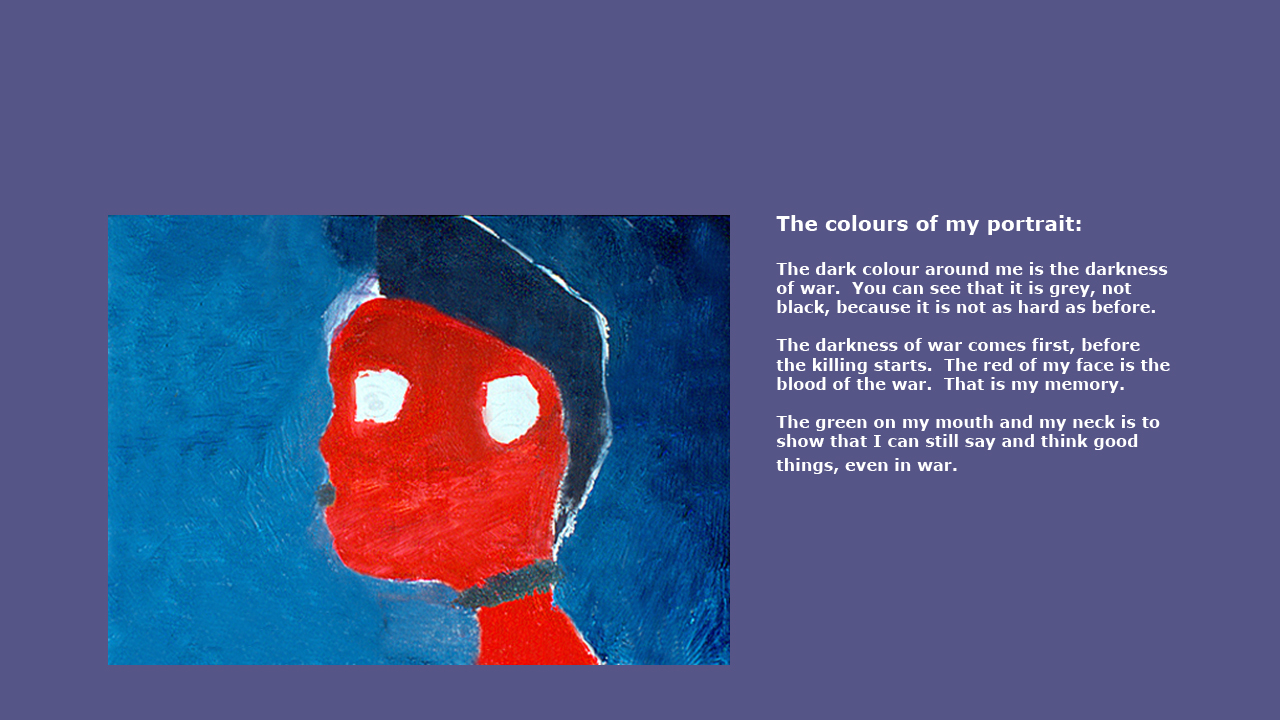

“Just before a war starts, there is a fog that comes down and surrounds people. It makes everything completely dark, it is impossible to see anything or know what is going on. People become very frightened and confused. This fear, this confusion, makes them lash out at others. They use anything they can find – knives, sticks, machetes, hammers. They kill because of their fear and confusion. That is when the blood comes, the red.”

“So war has two colours: black and red. The black is for the darkness of war. The red is for the blood that is shed.”

This was a war based in ethnic tensions, power struggles and competition for resources and control. Rwanda has three main ethnic groups: Hutus (approximately 85% of the population); Tutsi (14%) and Twa (1%).

After World War I, Rwanda fell under the control of the Belgian government who, in turn, gave considerable power and privilege to the Tutsi population. This provoked a deep resentment by the Hutu majority. Following WW II, the Hutu people began to gain some measure of power, partly through support from the Roman Catholic Church. Over the next 45 years there was a succession of struggles and short civil wars as the two ethnic groups competed for control.

It is difficult to identify a precise date when the Hutu Power Movement set in motion its plan to eliminate the Tutsi population. However, by 1993, many of the preparations were in place. Hutu Power compiled a list of “traitors” whom they planned to kill. They were stockpiling weapons and undertook a rigorous training of youth in civil defence as well as the promotion of Hutu pride and Tutsi hatred

It was later shown that policymakers in France, Belgium, the United States and the United Nations were aware of these preparations for massive slaughter but failed to take steps to prevent it.

The killing actually began shortly after April 6, 1994, the day when a plane carrying Rwandan President Habyarimana, a Hutu, was shot down. The Hutu leadership sent out a call, often through radio messages, for the population to rise up against “the Tutsi cockroaches”. The Hutu population, many of them youth, responded with great zeal. Tutsi and people suspected of being Tutsi were killed in their homes and at roadblocks. Entire families were killed together. Women and girls were systematically and brutally raped. Streets were flowing with blood.

In just under 100 days 800,000 people were killed, comprising 70% of the Tutsi population and 20% of Rwanda’s total population. It is estimated that 200,000 people participated in the perpetration of the Rwandan genocide. The international community remained silent.

The genocide finally ended when the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), led by Paul Kagame, the current Rwandan President, defeated the Rwandan government forces. To a large extent the genocide had burned itself out by this time. But the country was in ruins and its rehabilitation has taken decades.

It began on April 1994.

Burning houses,

Killing Tutsis, Tutsis,

From every place and everywhere.

Blood spreading over the hills.

People fleeing:

In the hills, in the valleys, in the churches.

And they were shouting:

“Kill more, kill more”

“Kill the cockroaches.”

Machetes, spears, knives,

Clubs with nails, anything.

People killed in the wildest way.

Children, parents, old people.

And the world was just looking.

They urged the killers, saying,

“Don’t worry. It is only a Tutsi

Their God has deserted them.

Their God is dead.”

Youth Collective Poem

Prior to the workshop a team of experts met to discuss and confirm the activities. Because of the sensitive nature of the topic and the background of the participants (all were orphans who were head of child headed households) there were many issues to consider. As well, the psychiatric unit of the Nyamata hospital was participating in the workshop to obtain information on children’s memories and mental health. The Department of Health was interested in using the results of the workshops in their training for community workers.

The first workshop (1997) included a one-day orientation with the youth participants. While they were eager to participate in the five day event, they were also concerned about their domestic responsibilities. It was agreed that all participants would receive two goats and also that childcare would be provided for their younger siblings. The participants were reassured that they could opt in or out of any activity. They agreed that the materials produced in the workshop could be used for education and training purposes.

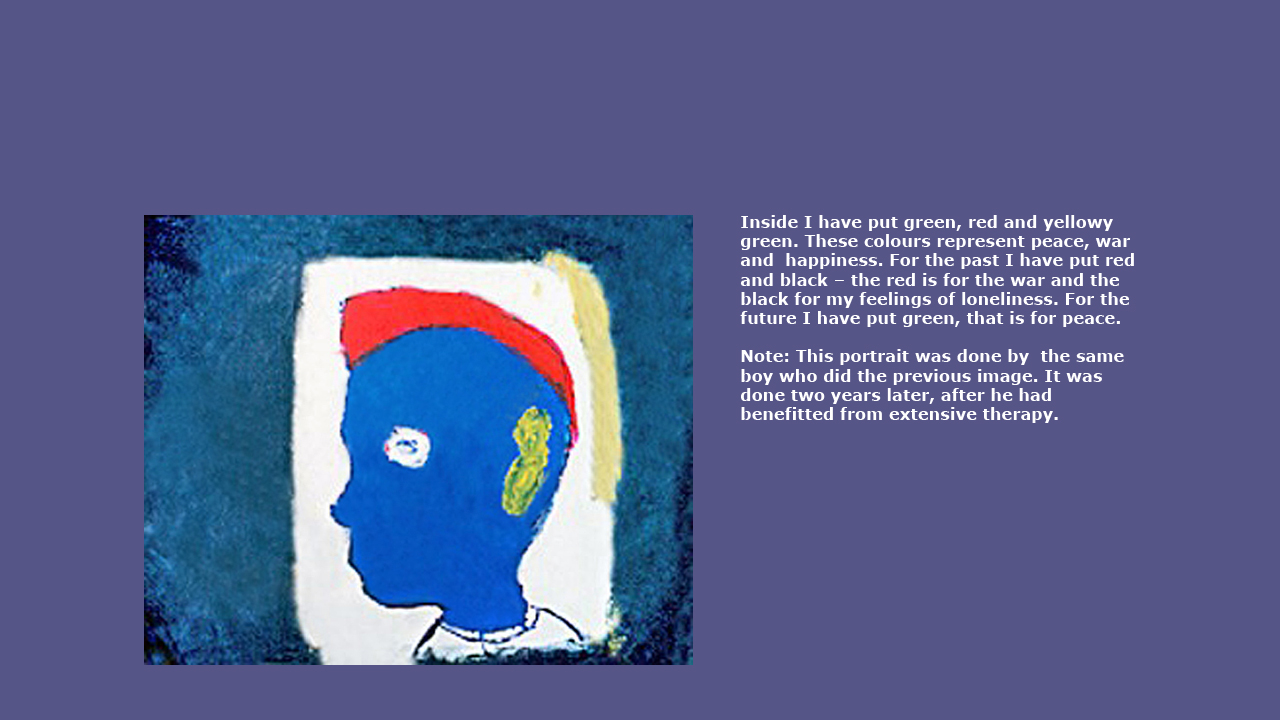

The second workshop (1999) included many of the same participants who had attended the first one. The process established for the first workshop was repeated, although new activities were added.

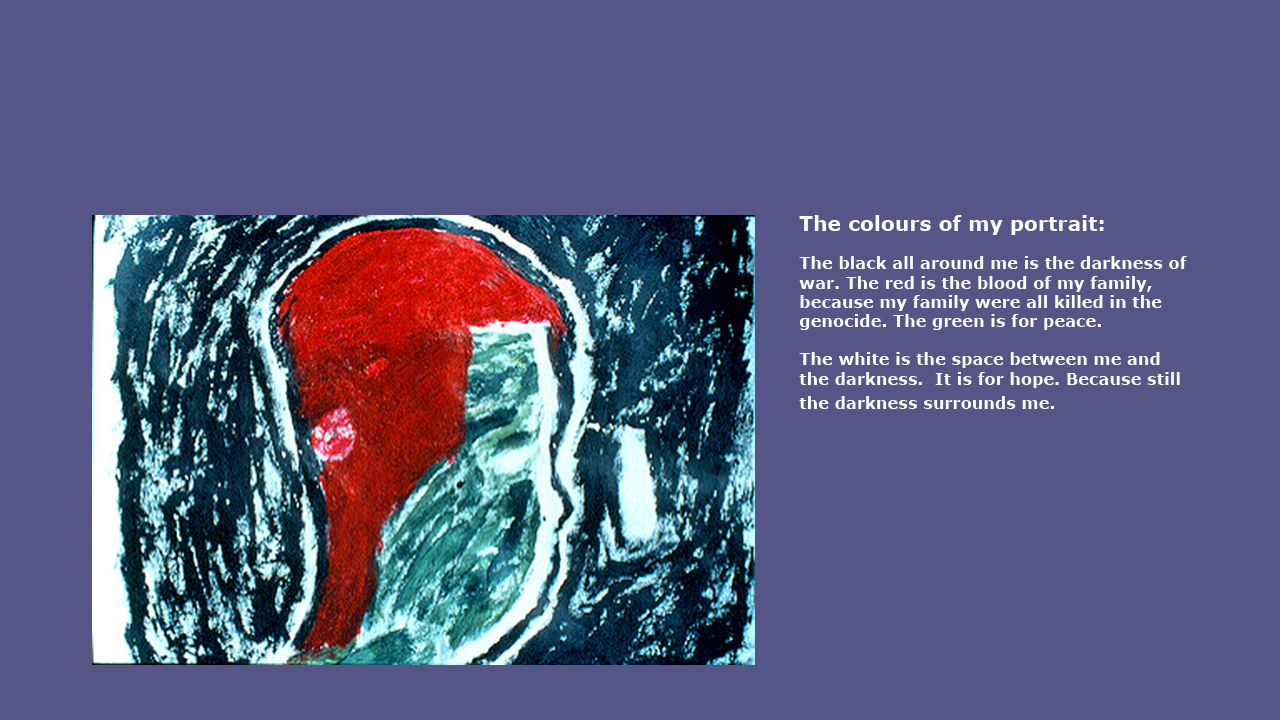

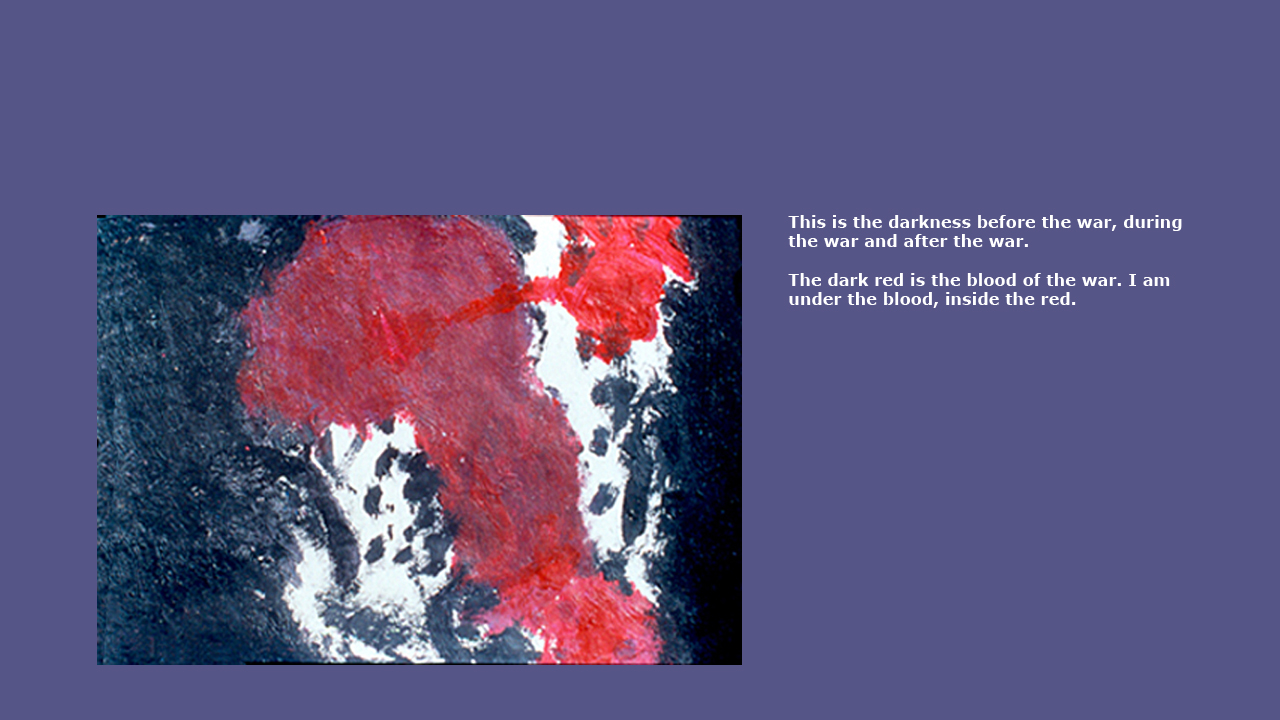

The workshops went well, though there were many intense moments, particularly in the first workshop. Each day representatives from the hospital reviewed the participants’ artwork. This resulted in one child being referred for special counselling (his pictures are included in this gallery). An exhibit of the participants’ work was shown to family members and community elders. Many adults openly wept and asked the children to forgive them for not being able to protect them from the genocide.

The second workshop ended with a one-day field trip to a children’s garden.

The images and writing produced in these workshops have been extensively used in education and training activities.